Colombian President Gustavo Petro signs a Pact for Land and Life; Revolution for Life, committing to carry out land redistribution, restitution, and recognition to enable rural working people to pursue economically and ecologically regenerative livelihoods. In this blog, Prof. Jun Borras and Itayosara Herrera discuss the implications of this pact.

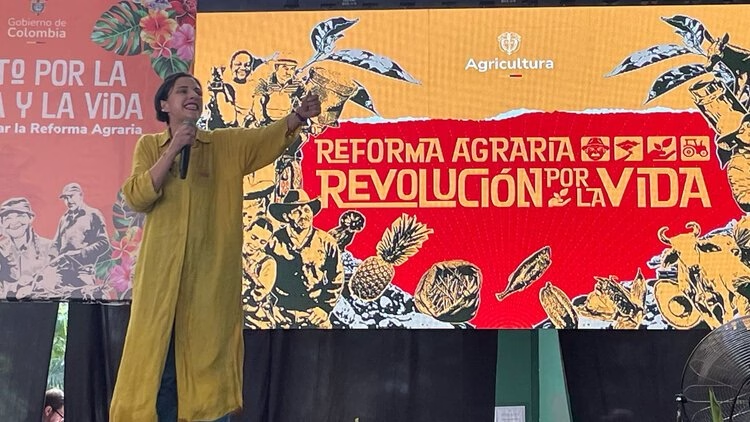

In February 2025, in Chicoral, Tolima, Colombia, 5,000 campesinos, Afrodescendants, Indigenous and government officials gathered for two days, and made a pact: Pacto fpr la Tierra y la Vida – Pact for Land and Life; Revolution for Life. The 12-point agreement signed by President Gustavo Petro and representatives of grassroots social movements revolved around the commitment to carry out land redistribution, restitution, and recognition to enable rural working people to pursue economically and ecologically regenerative livelihoods, with meaningful representation. The Chicoral event tries to undo a past in Colombia, and confronts a difficult challenge in the present world.

Undoing the past

In 1972 in Chicoral, landed elites and traditional political parties conspired to dismantle the 1960s redistributive land reform. They pushed to relax the criteria for defining unproductive land and inadequate land use to effectively avoid expropriation. This agreement became known infamously as the Pacto de Chicoral. It marked the definitive burial of Colombia’s redistributive land reform. It was, in essence, a pact of death—the death of land reform in Colombia—whose consequences continue to shape society today. Instead of redistribution, Colombia experienced more than half a century of counter-land reform, which led to increased violence in rural areas and the unprecedented expansion of the agricultural frontier with internal colonization in lieu of redistribution. This would also contribute to the rise of coca cultivation under the control of narco syndicates. Ultimately, it fed into the divide-and-rule strategy of the elites toward campesinos, Indigenous, and Afrodescendants.

Chicoral2025 is historic as it flips Chicoral1972: from the death of land reform to a commitment to redistributive land policies. It is ground-breaking as it is a pledge for a common front of struggles for land among campesinos, Afrodescendants and the Indigenous, aspiring to put an end to the divide-and-rule tactic employed by counter-reformists.

Confronting current challenges

The contemporary climate of land politics is extremely hostile to redistributive land policies, reflected in the continuing global land grabs. The condition is marked a global consensus among reactionary forces celebrating land grabbing, while maligning redistributive land reforms, as exemplified in Trump’s plan for the Gaza land grab while rejecting a modest liberal land reform in South Africa that land reform advocates in that country are not even happy about.

This current condition did not emerge from nowhere. It is a direct offshoot of decades of neoliberalization of land policies. The neoliberal consensus has deployed coordinated tactics.

- First, rolling back gains in redistributive land policies, largely through market-based economic policies hostile to small-scale farmers.

- Second, containing the extent of implementation of existing redistributive land policies where these exist.

- Third, blocking any initiative to pass new redistributive land policies in societies where these are needed.

- Fourth, reinterpreting existing laws and narratives away from their social justice moorings and towards free market dogmas; thus, land tenure security means security for the owners of big estates and capital.

- Finally, all four are being done in order to promote market-based, neoliberal land policies: justification and promotion of market-based land policies, formalization of land claims without prior or accompanying redistribution which simply ratifies what exists.

When neoliberalism gained ground in the 1980s, among the first casualties was redistributive land policies. The heart and soul of classical land reform were:

- (a) land size ceiling, a cap to how much land one can accumulate and

- (b) the right to a minimum access to an economically viable land size, or land for those who work it.

Today, land size ceiling is a taboo. Thus, programmes for providing minimum access to land to build-scale farms have difficulty finding land to redistribute.

During the past four decades, there have been only a handful of countries that managed to pursue redistributive land reforms: Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, the Philippines, and Zimbabwe. Significant programs have provided collective land titles for the Indigenous such as the one in Colombia, although many of these lands are in isolated, marginal geographic spaces.

The more common accomplishments are a variety of petty reforms. Small reforms are not inherently good or bad, and they are good especially when they provide immediate relief to ordinary working people. They constitute ‘petty reformism’, a negative term, when small reforms were done in lieu of systemic deep reforms. Thus, limited land titling, formalization of land claims, and individualization and privatization of the commons – often labeled under a misleadingly vague banner: land tenure security, which is often about the security of the owners of big estates and capital.

Globalizing Chirocal2025

The need for land redistribution, restitution and recognition remains urgent and necessary, for Colombia and the world. This is even more so in the current era when dominant classes other than agrarian elites aggressively grab land from peasants and Indigenous: profiteers behind market-based climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies, corporate actors in renewable energy sector, global food system giants and financial capital. The forces against reforms have multiplied. But so as the potential forces in favour of reforms. The main alliance for redistributive land policies today is no longer limited to agrarian classes and state reformists; rather, it has to necessarily include social forces in food, environmental and climate justice, as well as labour justice, movements and struggles.

In 1979, FAO convened in Rome the World Conference on Agrarian Reform and Rural Development (WCARRD) hoping to bring new energy to global land reformism. The following year turned out to be beginning of the end of classic land reforms as neoliberalism kicked in and put an end to state-driven redistributive land policies. In March 2006, FAO convened a follow-up to WCARRD, the International Conference Agrarian Reform and Rural Development (ICARRD) in Porto Alegre, Brazil, with the goal of reviving efforts at democratizing land politics. The following year, the global land rush exploded that led to the dispossession of millions of peasants and Indigenous worldwide. In February 2026, twenty years after Porto Alegre, ICARRD+20 will be convened by the Colombian government. It is a very timely international initiative. Chicoral2025 signals what kind of agenda the Colombian government wants to emerge at ICARRD+20: a deep commitment to democratic land politics for regenerative renewal of life.

Several researchers from the ISS-based ERC Advanced Grant project RRUSHES-5 and the Democratizing Knowledge Politics Initiative under the Erasmus Professors program for positive societal impact of Erasmus University Rotterdam are engaged in the Pact for Land and Life process.

About the Authors:

Saturnino (‘Jun’) M. Borras Jr. is a Professor of Agrarian Studies at the International Institute of Social Studies (ISS), The Hague. He served as Editor-in-Chief of the Journal of Peasant Studies for 15 years until 2023 and is part of the Erasmus Professor Program for Societal Impact at Erasmus University Rotterdam. He holds an ERC Advanced Grant for research on global land and commodity rushes and their impact on food, climate, labour, citizenship, and geopolitics. He is also a Distinguished Professor at China Agricultural University and an associate of the Transnational Institute. Previously, he was Canada Research Chair in International Development Studies at Saint Mary’s University (2007–2010).

Itayosara Rojas is a PhD Researcher at International Institute of Social Studies (ISS), Erasmus University Rotterdam. She is member of a European Research Council (ERC) Advanced Grant awarded project “Commodity & Land Rushes and Regimes: Reshaping Five Spheres of Global Social Life (RRUSHES-5)” led by Professor Jun Borras. As part of this project, Itayosara examines how the contemporary global commodity/land rushes (re)shape the politics of climate change, labour, and state-citizenship relations in the Colombian Amazon.

Are you looking for more content about Global Development and Social Justice? Subscribe to Bliss, the official blog of the International Institute of Social Studies, and stay updated about interesting topics our researchers are working on.

Fabio Andres Diaz Pabon is a Colombian political scientist. He is a research associate at the Department of Political and International Studies at Rhodes University in South Africa and a researcher at the ISS. Fabio works at the intersection between theory and practice, and his research interests are related to state strength, civil war, conflict and protests in the midst of globalisation.

Fabio Andres Diaz Pabon is a Colombian political scientist. He is a research associate at the Department of Political and International Studies at Rhodes University in South Africa and a researcher at the ISS. Fabio works at the intersection between theory and practice, and his research interests are related to state strength, civil war, conflict and protests in the midst of globalisation.

Sanele Sibanda is a faculty member in the School of Law at the University of the Witwatersrand in South Africa. He has been a visiting fellow at ISS, a participant in the joint Erasmus School of Law – ISS Project on Integrating Normative and Functional Approaches to the Rule of Law, and currently serves in the supervisory team of one of the candidates in a

Sanele Sibanda is a faculty member in the School of Law at the University of the Witwatersrand in South Africa. He has been a visiting fellow at ISS, a participant in the joint Erasmus School of Law – ISS Project on Integrating Normative and Functional Approaches to the Rule of Law, and currently serves in the supervisory team of one of the candidates in a