Bigotry, in all its forms, is steadily rising. Clearly, being non-racist is not enough; we need to be anti-racist to be able to combat race-related bigotry once and for all. This principle should indeed apply to all forms of bigotry, including antisemitism. However, as this article explains, misleading narratives in the documentary film Viral: Antisemitism in Four Mutations distort our understanding, and even serve as a cover, for other forms of intolerance, which can move us closer to bigotry instead of further away from it.

Anti-black racism, antisemitism, Islamophobia and other forms of bigotry are on the rise in Europe and elsewhere in the world, according to annual reports of the European Commission Against Racism and Intolerance. As a result, people are rising up in protest through #BlackLivesMatter and other movements. The global outcry and calls for change following the police killing of George Floyd vividly reveals just how prevalent racism still is. Yet, it is also clear how some organizations purporting to challenge such hate crimes can use an anti-racist message as “cover” for other forms of bigotry and intolerance, as a recent documentary has also done.

Antisemitism in films and documentaries

In cinematography, antisemitism, like other forms of bigotry, often has been afforded special attention. As a Jewish youth growing up in my congregation, I watched many of these movies dealing with antisemitism—from classics such as Ben-Hur (1959) to the more recent Schindler’s List (1993). One of the most recent and acclaimed documentaries I saw was the bold 2009 film Defamation by Israeli film-maker Yoav Shamir. I was therefore curious about how antisemitism was dealt with in the recently released documentary Viral: Antisemitism in Four Mutations by the American film-maker Andrew Goldberg. However, I felt very dispirited after watching it. Rather than meaningfully addressing the very real problem of antisemitism in the world, this documentary reproduces misleading narratives that distort discourses on antisemitism.

In this article, I will explain how the film-maker argues that there is a moral equivalence between four different forms or “mutations” of antisemitism and what’s wrong with this conceptualization of it.

Four “mutations” of antisemitism

Viral: Antisemitism in Four Mutations attempts to show how four different examples of antisemitism manifest in present-day society and the “logics” that purportedly drive antisemitism. The documentary is intended to provide what the film-maker regards as an honest view of antisemitism, but is so unbalanced that it ends up having the opposite effect.

In Part I of the movie, the focus is on the Far Right in the USA. After very moving, personal testimonies by victims of various violent antisemitic attacks, the documentary turns to an interview with a Mr. Walker, who is running for the state legislature in North Carolina. Walker insists that “God likes whites more than blacks”, argues that black persons and Muslims are the same, and finally reproduces a typical antisemitic conspiracy trope that “the Jew was created to destroy white Christian nations”. George Will, a prize-winning Washington Post columnist, then sums up the perverse “logic” behind antisemitism: “In a healthy society that has problems, people ask ‘what did we do to cause this’? In an unhealthy society that has problems, they say ‘who did this to us’? And the Jews are always a candidate.”

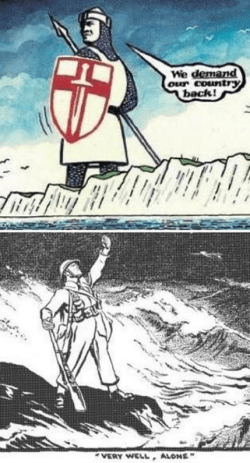

In Part II, the focus is on a smear campaign by the right-wing, nationalist president of Hungary, Victor Orban, aimed at the liberal Hungarian-American businessman and philanthropist George Soros. Classic antisemitic tropes are invoked, presenting clear examples of antisemitism through the use of grotesque cartoons and photoshopped images of Soros with exaggerated Judaic features. Moreover, the Hungarian media juxtaposes images of Muslims entering the country against accusations that they are “inundating your culture” and, moreover, are part of a “Soros plan”. Posters, billboards and television ads all reinforce these patently antisemitic and Islamophobic messages.

I am disgusted. However, something crucial is missing. While examples of antisemitism by Orban and others in his government are well established, paradoxically, as one interviewed professor notes, Orban does not want to be accused of antisemitism. Indeed, “he wants to pose with ‘them’—he even wears the hat”. Why is it, then, that Orban, his political party and the Hungarian government crudely reproduce antisemitic tropes while simultaneously object to being called antisemitic? The film-maker doesn’t address this crucial issue at all, also avoiding Orban’s very public cultivation of diplomatic ties with the State of Israel.

Further omissions are apparent in Part III of the film, which purports to focus on antisemitism among the “Far Left” in the United Kingdom. There is no mention of antisemitism within the Conservative Party. The focus is squarely on the Labour Party. The accusation is that Labour’s alleged antisemitism problem is due to “left-wing extremists” who condemn capitalism, criticize Israel and therefore by definition are antisemitic. This is both highly unconvincing and inflammatory, reinforced by interviews with embittered former Labour members who are also vocal supporters of Israel (and neo-liberal economic policies), such as former Labour leader Tony Blair.

Totally unaddressed are what these so-called “left-wing extremists” criticize, namely Israel’s discriminatory and brutal policies against Palestinians that have been labelled as an “apartheid regime”. While maintaining its thin claims against “leftists”, the film-maker fails entirely to engage with the many critics of these claims, such as Jamie Stern Weiner or Mehdi Hasan. Or with a comprehensive report on distorted media coverage of the Labour Party by Dr. Justin Scholsberg of Birkbeck College and journalist Laura Laker. Or with the book Bad News for Labour: Antisemitism, The Party and Public Belief by award-winning journalists and academics Greg Philo, Mike Berry, Justin Scholsberg, Antony Lerman and David Miller. To name but a few.

Part IV focuses exclusively on what the filmmaker describes as “Islamic radicalism” in France. The primary perpetrators of antisemitism, it is claimed, are “Islamic extremists”. Brief reference is made to what is described as “France’s colonial experiment”, which led to hundreds of thousands of Muslims to move to France. The implication is that those suffering from “post-colonialism” have a problem. Rather than acknowledge the country’s expansive Islamophobia, the film-maker plays directly into it, asserting that, based on “surveys”, one-third of Muslims in France are antisemitic, as compared with ten percent of non-Muslims. The suggestion that Muslims are far-more inclined than anyone else to hate Jews is both unsubstantiated, based on anecdotal examples and utterly fails to address the historical context of both antisemitism and Islamophobia.

Time for a serious discussion about antisemitism

As the film does reveal, there is clearly a problem of antisemitism (as well as Islamophobia, racism and other forms of bigotry and intolerance), deserving of a serious discussion. However, the film is so filled with distortions that it doesn’t help to really understand, let alone combat this problem.

The film’s fatal flaw, noted elsewhere by Michelle Goldberg, is its conflation of criticisms of Israel and antisemitism. Indeed, this becomes a conspiracy theory of its own that “people hate Israel because they simultaneously hate the Jews, capitalism, and Western democracy”. Moreover, by interspersing credible examples of antisemitism with highly questionable examples, the selective treatment of these four “mutations” and the drawing of a moral equivalence between them critically undermine the very important goal of addressing antisemitism.

The need for critical reflection

The global fight against bigotry must be taken seriously. Hence, a serious and balanced documentary about antisemitism would be something different entirely. It would acknowledge the context of antisemitism as being part of a broader pattern of hatred, intolerance and discrimination affecting many persecuted groups. It would include constructive criticism of the film-maker’s assumptions. And finally, it would not make simplistic and distorted assumptions that critics of Israel’s expansionist, colonial and discriminatory regime are de facto antisemitic.

About the author:

Jeff Handmaker is a senior researcher at the International Institute of Social Studies (ISS) and focuses on legal mobilisation.

He is a regular author for Bliss. Read all his posts here.

About the author:

About the author:

Representing a move away from Eurocentric books on the topic, the Research Handbook offers relevant and focused contributions that provide three valuable lessons for current and future policies. First, in addition to the full coverage of positive interactions, our contributors also explicitly consider the impact of negative interaction. Second, the Research Handbook in addition to the analysis of OECD markets provides a comprehensive set of detailed empirical analyses of developing and emerging economies in Africa, Asia and Latin America. The contributions by 31 leading experts from industrial nations, emerging economies and developing countries in five continents provide a unique perspective on both the heterogeneous dynamics of economic diplomacy and the tools to analyse the impact and efficiency of economic diplomats both qualitatively (case studies, interviews) and quantitatively (macro-economic gravity models, micro-economic firm level data, surveys, meta-analysis, cost benefit analysis). Third, the Research Handbook provides detailed discussions of information requirements, data coverage and the impact of (changes in) the level and quality of diplomatic representation. The studies in the Research Handbook thereby reveal how and under which conditions economic diplomacy can be effective, providing clear guidance for evidence-based policy.

Representing a move away from Eurocentric books on the topic, the Research Handbook offers relevant and focused contributions that provide three valuable lessons for current and future policies. First, in addition to the full coverage of positive interactions, our contributors also explicitly consider the impact of negative interaction. Second, the Research Handbook in addition to the analysis of OECD markets provides a comprehensive set of detailed empirical analyses of developing and emerging economies in Africa, Asia and Latin America. The contributions by 31 leading experts from industrial nations, emerging economies and developing countries in five continents provide a unique perspective on both the heterogeneous dynamics of economic diplomacy and the tools to analyse the impact and efficiency of economic diplomats both qualitatively (case studies, interviews) and quantitatively (macro-economic gravity models, micro-economic firm level data, surveys, meta-analysis, cost benefit analysis). Third, the Research Handbook provides detailed discussions of information requirements, data coverage and the impact of (changes in) the level and quality of diplomatic representation. The studies in the Research Handbook thereby reveal how and under which conditions economic diplomacy can be effective, providing clear guidance for evidence-based policy. About the authors:

About the authors:  Selwyn Moons has a PhD in economics from ISS. His research focus is international economics and economic diplomacy. Selwyn is currently working as Partner in the public sector advisory branch of PwC the Netherlands. Previously he worked in the Dutch ministries of Economic Affairs and Foreign Affairs.

Selwyn Moons has a PhD in economics from ISS. His research focus is international economics and economic diplomacy. Selwyn is currently working as Partner in the public sector advisory branch of PwC the Netherlands. Previously he worked in the Dutch ministries of Economic Affairs and Foreign Affairs.

Peter van Bergeijk

Peter van Bergeijk